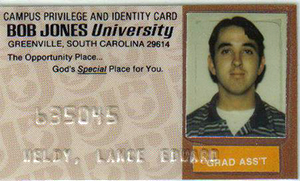

Lance Weldy Graduate Assistant ID

Part 2: Queer Life at BJU and My Expulsion

Read Part One Read Part Three Read Part Four Read Part Five

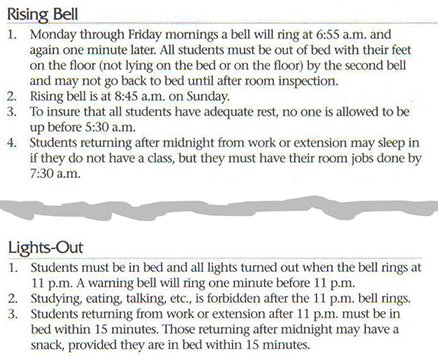

I cannot overstate the excitement I felt when I first attended BJU. This was my chance to really begin my young adult life, to really enjoy the Christian peer interaction I had long since craved. Over the course of my first year there, I had to make some serious adjustments in how I spent my time. Some of that happens on most college campuses, but for BJU, that time management issue became exacerbated when you factor in the “Rising Bell” and “Lights-Out Bell” of the dorms and the many events we were required to attend.

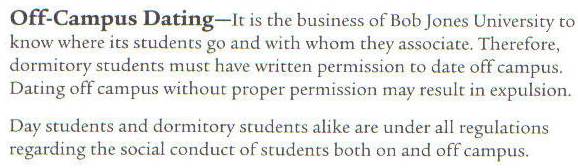

excerpts from BJU Dormitory Handbook 1997, Pages 2 & 3

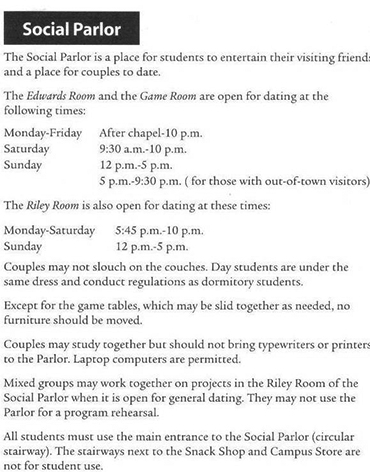

BJU Student Handbook 1997, Page 44

Though the campus was relatively small, meeting strangers at the Dining Common or other places was not unusual, and I learned the art of social interaction on a friendship level, but I could never seem to make the transition to anything more than that with girls. I knew I wanted and was expected to have a girlfriend, so I began to wonder how I would find one and find the courage to ask her out. Fortunately, BJU promoted itself as “The Opportunity Place,” which I always interpreted as referring to the dating possibilities (it was no secret that many women were there to get their “MRS.” degree) in the way it manufactures social gatherings all semester long. Outsiders may be even interested to know that BJU was so obviously pushing us to date that they had a designated “Dating Parlor” in the student mall area and also required every “Greek” literary society—the BJU version of fraternities and sororities which all students were required to join at the beginning of their freshman year—to have a “Dating Outing” once a year.

[slideshow_deploy id=2833]Bob Jones University’s dating parlor through the decades (1940s — present day)

I thoroughly enjoyed and participated in the literary society I joined—I purposefully chose the one my father had been in—so I made sure to attend each dating outing and was also asked throughout my undergrad years to the occasional dating outing from a female friend here and there, but these moments never lead to anything serious. Moreover, BJU combines on-campus cultural events with social ones, and highly encouraged you to attend these with a date: anything from Bible Conference church services, sporting events, student recitals and performances, and, most importantly, the Artist Series, which was either some classic play or opera or special concert production. These were exclusively designed for you to dress up and take a “special girl” out as if on a date, which began with walking over to the girl’s dorm and “picking her up,” taking pictures, and then walking her to the concert venue.

BJU Dormitory Handbook 1997, page 25

In the late 90s, my friends and I were cognizant that the dating environment on campus had transitioned from the serious one-on-one style of our parents’ generation to a more informal “group dating,” where groups of guys and girls would attend events together. There was even less stigma attached to a group of guys or girls going to these events without the opposite sex. (Though no one ever really said it, it felt like we were viewing these events as more of a requirement to fulfill rather than as an “opportunity,” especially when these events would be scheduled at inconvenient times, like during the school week.) For the most part, I wanted to participate in finding this “opportunity” and would make an effort in taking a girl, but as much as I wanted the concept of a serious date, I never felt a real physical connection. It didn’t help that I was extremely shy in this scenario, and I probably was using my lack of dating experience in high school as an excuse for myself, but more than likely, I really wasn’t more aggressive in actively dating a woman, even in a fundamentalist environment, because the physical drive just wasn’t there.

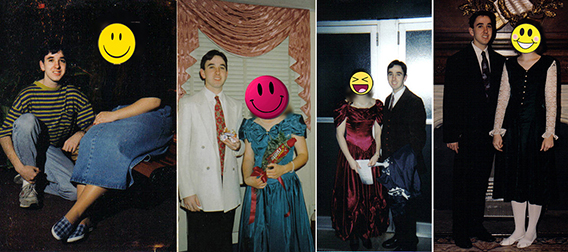

Lance with several of his Artist Series and Society Dating Outings dates,

(these women’s faces have been covered to preserve their anonymity)

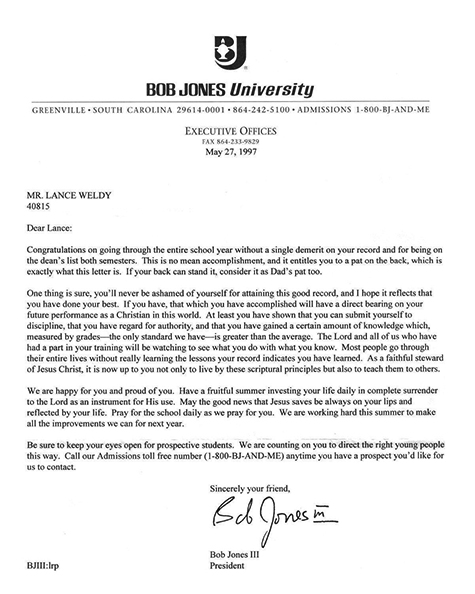

Before I knew it, I was an upperclassman, and I started to hear a faint voice of disappointment in the back of my head. My parents had gotten married right after graduation, and with no serious prospects, I was nowhere near their established schedule. (By this time, my older brother had already followed in my parents’ footsteps and married soon after college; my younger brother would eventually do the same.) The fundy-queer part of me was quite indulged upon receiving a glowing letter from the university president that commended me for accruing no demerits for the entire year. I wouldn’t admit it openly, but I thought having a certain amount of leadership at BJU would be a little gratifying. After all, I was proud that my father had been a hall leader in the dorms when he was there. All I needed was to date the right girl in order to complete the persona they were looking for. But while I was having no luck with the opposite sex, I was developing a great platonic friendship on campus with a guy in my society, and also meeting my physical needs with non-BJU guys off campus. As an upperclassman, I had a car that I could park on campus, which opened up unexpected opportunities off campus that I soon began to crave and capitalize on more and more. On various evenings, I would frequent the mall or other places I knew where I could find the means to satisfy my physical drive with men, but I was always careful never to meet anyone affiliated with BJU or to disclose my experiences with anyone I knew on campus. This was purposely done to bifurcate my two opposing queer identities and to ensure that no one at BJU would know about this side of me. Even at this point in my time at BJU when I was still a fervent, optimistic defender of the university, I knew that rules were strongly enforced. Students had been “shipped” for attending innocuous, unchaperoned, co-ed parties off campus.

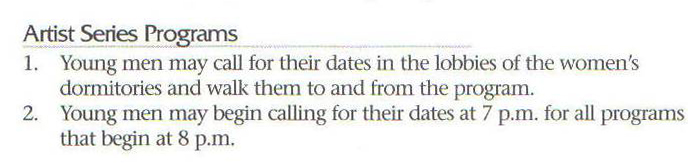

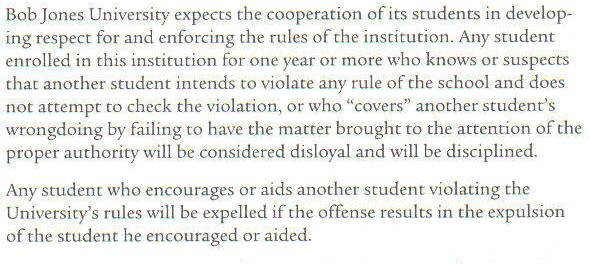

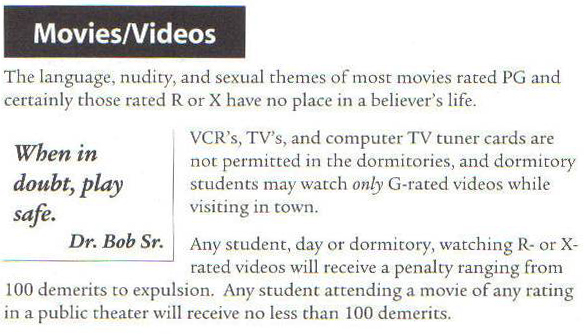

BJU Student Handbook 1997,Page 28

I was well aware that at times, especially during Bible Conference week, when—through the intense daily schedule with little sleep and many “convicting” sermons—students are being pressured to confess any sins, many would feel guilty and turn themselves and their friends in for anything that was against the rules, which could be as simple as listening to the wrong kind of music or watching any movie over a G rating.

I knew that no matter how much I trusted anyone on campus, there was always the possibility he or she could be forced to use this information against me. Damning information was the cultural capital for opportunistic students: therefore, turning people in to the various forms of administration was commonplace, especially when it was advantageous for advancement in the spiritual-leadership hierarchies on campus. Moreover, as we all were told and expected to know from the Student Handbook, if anyone was aware of another student’s breaking the rules, that person would also be eligible for the same punishment if it could be proved that he or she knew but did not tell.

BJU Student Handbook 1997, Page 5

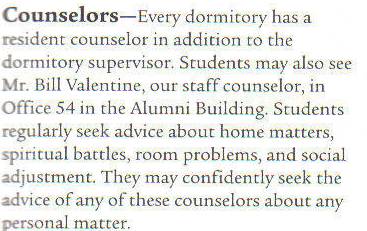

Needless to say, I remained closely guarded about this part of me. Furthermore, for the sake of argument, had I ever seriously considered taking advantage of confiding in my dorm counselor about being spiritually depressed because of my gay-queer identity, I knew not only that what I said would not be kept confidential, but I also knew I would be red-flagged forever in the eyes of the administration.

BJU Student Handbook 1997, Page 51

In Justin VanLeeuwen’s post, he really sets up a nice imagery for how I felt: “In another environment I might have been able to seek help and counsel from peers and adults. But in fundamentalism [. . .][,] a reputation (so I heard countless times) is like a pane of glass that, once broken, can never be repaired (one failing, particularly of a sexual nature, can forever disqualify a person from various ministry opportunities); [. . .] to be suspected of a spiritual problem or to admit to one by way of seeking help results in a loss of trust and that prized reputation as well as a re-categorization as a deviant [. . .].” I felt exactly like that fragile pane of glass and did not want to do anything to upset the precarious balance between my two different identities. So I kept my mouth shut.

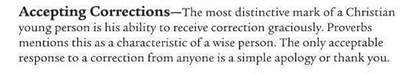

Without getting too much into a discussion about Althusser’s Ideological State Apparatuses (ISA), I do want to briefly mention how his theoretical structure serves as a conceivable paradigm for how BJU—with all its constituents— operates. When I teach young adult literature, we talk about how power is wielded over and passively accepted by members of different communities, and one of the lenses through which we discuss this phenomenon is Althusser’s ISA, which refers to any social institution that controls this sort of ruling power through ideology (rather than brute force). According to Althusser, some more notable examples of ISAs include churches and schools (page 143). As Roberta Seelinger Trites paraphrases, ISAs are “institutions [that] have a self-perpetuating interest in instilling their ideologies into the masses in order to retain their hegemony” (page 4). In other words, in order for these socially-constructed institutions to survive, they must keep reinforcing their ideologies both overtly and subtly. Althusser remarks that in “the pre-capitalist historical period [. . .], it is absolutely clear that there was one dominant Ideological State Apparatus, the Church” (italics in original, page 151), but that“the Church has been replaced today in its role as the dominant Ideological State Apparatus by the School” (italics in original, page 157). In the case of BJU, the hegemony becomes compounded because this social institution is multivalent: not only does it serve in loco parentis as a university figure, but it also serves in loco ecclesia as the community church. Consequently, it became difficult to distinguish whether the punishments, such as receiving demerits for missing a class, were meted out as academic penalty or as spiritual rebuke for disregarding authority. Of course, we were always told that BJU was “God’s Special Place for You,” so any action of theirs, academic or not, was done in the name of spiritual ministry, which labeled any potential questioning as rebellious. Accordingly, we were supposed to passively welcome correction.

BJU Student Handbook 1997, Page 16

At a place where we were constantly reminded that our spirituality was determined or evidenced by the amount of work that we put into evangelism and ministry-oriented activities, I could never effectively discern which came first: the faith or the works, or, more importantly, which spurred which, because we were constantly asked to question ourselves and our motives, to really ask if we were saved. It is no wonder that the ideological messages that BJU instilled both in the classroom and in chapel served as a means to perpetuate my divided and repressed self.

Alternately, and perhaps ironically, I had developed a pretty strong, platonic connection with a guy in my literary society who shared many similar interests in music and culture. Andrew Bolden and I were the same age and from the Midwest, went on the same extension ministry for awhile, and even worked in the same department on campus, so we began to spend a lot of time together. Throughout our friendship, we talked about our future goals and desires, which even included the kind of woman we wanted to marry and how we wanted our weddings to be, but never did we talk about anything even remotely suggestive of being attracted to guys. Suddenly, during the second semester of my senior year (1998), I received startling news from someone I was very close to on campus. She basically told me that she was hearing unsavory rumors about Andrew and me, and while she didn’t tell me to do anything other than “be careful,” I knew it was coded language that I should distance myself from Andrew and the negative reputation that I had been unknowingly creating for myself. I began to feel fear and uneasiness not only because I was not good at confrontation or interpersonal conflict; more importantly, I froze inside at the thought that people could be thinking that I might be gay. I wasn’t fooling myself into thinking that I was Schwarzenegger masculine. Instead, I liked to believe I exuded a “safe” masculinity akin to someone like Dick Van Dyke: someone musical, sensible, conservative, friendly, garrulous, and, most importantly, non-threateningly straight. But maybe I was fooling myself even then. Furthermore, I understood that rumors were dangerous on campus; they begat seemingly innocuous conversations with hall leaders and dorm counselors, which in turn could put me on their watch list if I said the wrong (or honest) thing. I was extremely impressionable and vulnerable and believed I was doing the right thing by distancing myself from Andrew, who was going through his own kinds of misery on campus. I regrettably caved in to pressure and shut him out of my life. To this day, I still cringe at my actions. For years afterwards, I managed to see Andrew briefly once or twice because of our similar social circles, but I knew I had severely hurt him and that it would be forever awkward between us. It wasn’t until last year, more than 10 years from the time I shut him out, that we met each other under the auspices of what would become BJUnity. Imagine our surprise and the five hour phone call that took place soon thereafter! I was so proud to read his own post on here and glad that we could repair the past. Andrew gave me permission to mention him in this post, and he remarked: “The irony of our relationship is that in spite of how we were so close, we kept our mutual struggle hidden even from each other. The beauty of our redeemed and renewed friendship blooms from our mutual embrace of our true selves and the rejection of the cult propaganda that oppressed us for so long.” I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Bob Jones, III’s 1997 letter to me, congratulating me for having received no demerits throughout the entire school year

Back in May 1998, I graduated with my bachelor’s degree and decided to stay on as a graduate assistant, partly because it was easier to stay (I hadn’t thought about graduate school elsewhere), and also because I was still holding on to the dream that I needed to remain at BJU to find the wife that God had for me. I really enjoyed the new privileges that this position afforded and hoped that my new circle of friends might lead me into a dating opportunity. But while my fundy-queer side set my endeavors on that, my gay-queer side was searching for more information about and interaction within the gay world. I soon found myself checking out gay-themed movies from Blockbuster and watching them in my dorm room, and I can remember never feeling comfortable with any Hollywood representations of gay life. In the back of my head, I thought, “I don’t want this life. Nothing good can come of it.” Just as I cringed at the lack of realistic representations of fundy-queer pastor’s families on TV, so did I resist being gay-queer because of a lack of self-identification in the gay culture that only seemed to include extremely fit, athletic, vapid, beautiful guys who were more than likely self-destructive or consumed with their own appearances. I knew I wasn’t that kind of gay person, but I hadn’t really seen any other kind represented in any media format that I could find. So even though I was meeting guys, I never identified as being gay-queer. I remember even writing during this time that I would not be gay by the time I reached 30. It seemed that I knew this kind of a life wasn’t for me and that I had no intention of being gay. I didn’t realize then that it wasn’t just a choice I could suppress or automatically turn off.

I even took my curiosity and courage a step further into the gay world by going to The Castle, the local gay club, by myself one night. I didn’t know what I would find or do there, having never been in one before, but I knew I wanted to know more about this world. I was so paranoid of the ramifications of getting caught that I made sure to park in an adjacent lot. My visit was filled with a conflicting mixture of fear of getting caught and longing to interact; consequently, I mostly kept to myself at the club. Aside from a mild scare from the administration the next day, I felt the visit was a success in the sense that it appeared no one had recognized me or turned me in.

To complicate matters, around this time, I broke a very important personal rule: I began to fool around with another graduate assistant. I can still remember the very first time my two queer worlds collided in the dorm room—I was physically shaking because I knew I was implicating myself as gay-queer to someone else just like me on campus. I was crossing a boundary with someone who knew the real me, and that was frightening. That wasn’t supposed to happen. I can’t tell you how many times I would purpose in my heart to end our subsequent meetings after feeling tremendous guilt and fear, only to be “tempted” yet again in what I knew ultimately felt good and desirable. I had no way to understand what was happening to me other than to consider it extremely shameful and despicable.

My mental state became even more conflicted when I received a visit from my parents near the end of January 1999. I wasn’t even aware that their visit was a discreet intervention until I was eating pizza at their hotel room and my dad’s face turned serious and asked about the gay websites I had visited on their computer while home over Christmas. My insides stopped and my eyes began to tear up. This full-on confrontation, no matter how gentle, was irrefutably damning. In high school, I had been caught by my dad with a gay-themed movie I had checked out of the public library, but I had made a feeble excuse that it was a mistake. Unlike then, there was nothing I could do to explain this away. Instead, I told them half the truth: that I was jealous of their attractiveness, that I wanted to look like that. What I didn’t say was that I also found them desirable. My father asked me if I had ever been with another guy. I immediately responded, “No.” It was a lie, but I couldn’t face them if they knew the truth. Sex with anyone outside of marriage was a major sin in our family, so being with another guy would’ve been more than they could bear to hear; the repercussions for the truth would’ve been unfathomable for me. Plus, I was scared about what that information could’ve done to my standing as a graduate assistant. Of course, my parents had enough evidence to present to the administration without any verbal admission on my part, but I didn’t want to add fuel to the fire. Fortunately, the answer I gave seemed to satisfy their questions, and I got the feeling that they wanted to deal with this privately rather than get the administration involved. As they returned home, I remember feeling a mixture of emotions: I felt like a failure for letting them down, I felt like a shameful idiot for tainting their computer, I felt extreme love that they would come all the way down to South Carolina to take care of matters as discreetly as possible, but I also certainly felt self-hatred and a desire to work on not being gay. I promised myself to keep my dad informed in the subsequent months at how I was going to reform my ways, but my physical meetings with the graduate student around this time certainly made any “progress” difficult.

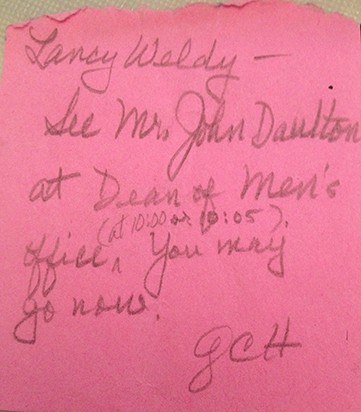

As it turns out, my two queer identities would converge again, but this time at the wrong place and the wrong time (if that’s possible), similar to how Thomas Hardy sets up the scenario between the Titanic and the iceberg in his poem, “The Convergence of the Twain.” Even now, this part of my life is painful to recount in detail, especially as I re-read my journal and relive this moment, so, for now, I will just be brief about the events. Essentially, one Thursday in early October 1999, I went to Furman University to do some research on a paper for class, but while at the computer, I also went to certain gay websites. It just so happened that a former or current BJU student (I don’t really remember which) was there as well and noticed what I was doing. He “confronted” me and told me that he was going to have to turn me in, so he asked me what my name was. In a panic, I lied and told him a fake name and went to my car soon after. But I knew things would never be the same for me; my time at BJU was over. Needless to say, I had difficulty focusing on much that happened for the rest of the day. By nightfall, my thoughts had intensified about every possible consequence from this, the most prominent: being expelled. I couldn’t sleep because I was trying to imagine every possible angle in which to construe this, but I came up short. I turned to scripture for comfort and began finding passages in Psalms that seemed to evoke similar emotions that I was feeling. The next day, Friday, I went to my classes as scheduled, wondering when I would get called in. It happened right at the beginning of my 10:00am class. I received a note from my teacher telling me to go directly to the Dean of Men, at which point I remembered my senses being heightened to everything while still feeling numb on my surreal walk over there. It was over.

Note from the Dean of Men

To this day, I regret not writing down everything specifically that happened in the Dean of Men’s Office. Maybe it was too painful for me or I was too busy getting my life sorted out afterwards. What I do remember is that my visit with Jon Daulton was punctuated into a morning and afternoon appointment because of a personal tragedy his wife was going through. Oddly enough, I thought this would bestow sympathy for me, too, but I was sadly mistaken. When I was finally told I had to be gone by Monday, I expressed my desire to stay, but to no avail. In an instant I had been transformed from a model BJU student/employee to someone who was apparently beyond their ability to reform. After the initial shock that this was really happening, I began to think my wounds were from God, that this was a sign that He still wanted me for His purpose, and that I should “glory” in His tough love; so when I knew I had to explain the news to my sister, who was just a BJU freshman at the time and who I was very close to, I felt completely broken, broken enough to admit the truth. I took her to Schlotsky’s just down the road from campus and told her I was being “shipped.” When I began to tell her the exact reason, she stopped me. She didn’t want to know. To this day I don’t know exactly why she stopped me, but, for whatever reason, that moment of providing clarity on my part was diffused, and I soon lost that courage to be fully forthcoming with anyone for at least another 10 years.

Unlike most people who are “shipped,” I was not “shadowed” by a hall leader for the rest of my time on campus. I assume it was because I was a graduate assistant. So, for approximately the next 36 hours, I occupied such a bizarre liminal space on campus: I was neither employed nor a registered student, unrecognized by the administration as anything other than reprobate or unclean; yet, I was still there, attending the soccer games with my sister as regularly scheduled. Word gradually spread that I was leaving. Most friends showed such support and love and compassion, even after I left; others kept asking for the reason I got expelled. I was too hurt and ashamed to tell any of them the real reason. I wonder now if any of them would’ve responded so supportively had they known. Oddly enough, my extended family in town and my campus roommate were both out of town for the weekend, so I did not have to do any serious explaining to either of them, nor did I have the opportunity to stay in town after that weekend even if I had wanted to. I called my mom, told her I got “shipped,” and asked if I could come home. I didn’t think they would have a problem, but I figured I should ask. Sunday came around, and I said my tearful goodbyes to close friends and my sister. That entire drive back up to Illinois, I could not stop thinking about the shame I had brought upon myself and the guilt I felt for abandoning my sister on campus. I had no clue what to do with myself or to tell my parents when I got back home.

Read Part One Read Part Three Read Part Four Read Part Five

Ed. Note: In Part Three, Lance details the despair that was the aftermath of his expulsion from Bob Jones University at home in Illinois.

7 comments

So proud of you, Lance. Proud to know you; proud to love you; proud to share this moment with you and call you friend. Your thorough documentation of the BJU experience will do much to bring the “outside world” into the realm of cultish oddity and its scope of control over our lives. Thank you for bringing your truth to the public forum: I’m certain that our stories are the unexpected catalysts for positive change.

Any reasonable person reading this part of your story will be able to see BJU for the neo-fascist autocracy it is. Where else is it not only acceptable but mandated that someone report you for what you view on a computer AT ANOTHER UNIVERSITY?! And the fact that you felt compelled to abandon a valuable friendship… Thanks for further exposing the lack of humanity at that place.

So very well written!!! I don’t think I realized you and Andrew were friends or at BJU at the same time. I still cringe at the four years I wasted there and the 7 more wasted years after that trying to live a lie. But we can’t regret our past as it makes up who we are! So proud to call you my friend!!

It really breaks my heart that you had to live with guilt and fear all those years. The environment at BJU, Grace Baptist, and other institutions caused my sister and I to both live in guilt, as well. It almost ruined my life, because I couldn’t live any longer feeling like such a horrible person. You have no idea all the people you will reach with your story and how many people look up to you because you are so brave to share the truth about your experiences in what I consider a cult. Hope you can feel the love!

A very thorough telling of life at BJU and congratulations on being open and honest in your story. I was a student at BJU at the height of the Vietnam war beginning my studies in 1969. Life at BJU was much stricter and conservative in the early 70’s than your time there and life as it is now. I’m always amazed at the changes that have taken place over a 40 year period, and how the university’s conservative stand continues to change and evolve.

I had no idea you experienced such pain back then, Lance. I always knew you were on a journey, and I’m so glad you’ve come so far! I’m proud to call you my friend and will never forget our awesome choir experiences together. Love you and thinking of you. Keep spreading the truth! It’s definitely making a difference!

Lance,

I am a Greenville person who came on your blog from a friend. My heart and love go out to you. I’m so glad you are on the road to healing and that you are sharing your story! I’m sure your concept of God has changed, but from my point of view He/She 🙂 honors your courage and loves you deeply.