Part 4: Coming Out to Myself

Read Part One Read Part Two Read Part Three Read Part Five

Lance Weldy, Ph. D.

While on the phone with the graduate director, my face became flush as it did when I was on the phone with Tony Miller. I was burning with shame and awkwardness, and was quite speechless at the unexpected question. How much detail do I go into? Should I tell him the truth? Will he understand that it’s a strict school? Will it hurt my chances of getting into the program?

5/6/01

“ I said I didn’t know if he knew much about Bob Jones, and he said yes he did, and I told him how it was very strict, and that I broke a rule and was asked to leave, but it had nothing to do with any legal reasons, that I didn’t break the law or do anything criminal. He said, so it wasn’t for any unethical or moral reasons in the workplace or anything like that—and I said no. [. . .] Then he said that that’s what he figured it was for. So, then he said he was going to give it back to the department and give his seal of approval for the graduate school to accept me. I couldn’t believe it. It was so nice to hear, though I wasn’t 100% sure until I could see it in writing.”

And just like that, the phone call was over. I was so thankful I did not have to go into any further explanation with him. He had even mentioned that getting expelled from BJU might not be as detrimental for me in the eyes of academia as I had feared, but because I still felt some allegiance and pride of being associated with BJU, I wasn’t sure if I believed him. Nevertheless, it was a huge relief for me to know that I was accepted!

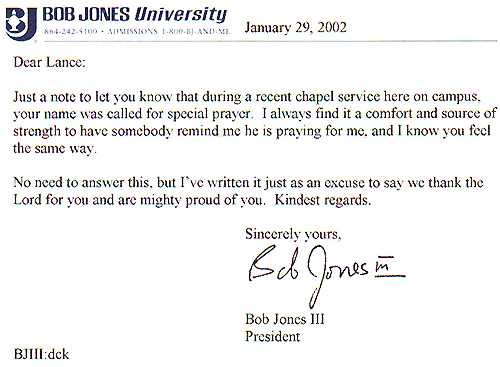

As I mentioned previously, part of my seeking validation as a forgiven, fundy-queer Christian was getting back into the fold of the BJU family, which is what I considered to be the pinnacle of Christian excellence. It may sound strange, but I wasn’t ready to recognize at this point in my life that my internal compartmentalization could not be resolved by simply existing in the BJU fold: that required some serious introspection which would not come until years later. But back in 2001, I was so thankful to be properly forgiven that I willingly re-submitted my membership dues for the alumni association. I remember sitting in the Writing Center in Texas in the early part of the Spring 2002 semester, elated to receive an email notification that my name had been mentioned for prayer in chapel.

letter from Bob Jones, III, indicating that Lance’s name had been mentioned in public prayer during a chapel service at BJU

This wasn’t a prayer from BJU that I would “get my heart right;” to the contrary, it was a prayer of support, and I have to admit that I secretly felt flattered by the attention and the approval. It was one more indication to me that, in the eyes of BJU, I was forgiven, validated, and on the right track again. But even with their seal of approval, I found myself inadvertently going through a routine that I would wind up repeating in different places over the next decade: I would move to a new home, determine that I was going to find an IFB church to be active in, and maintain at work a superficial image of a fundy-queer, conservative Christian. Invariably, I wound up visiting a few IFB churches several times here or there (recommended through a directory of “approved” churches I would request through BJU), but then, after a few months, I would drift away—attributing it to the lack of a “connection” to the people or the music or the preaching or whatever—and end up spending my weekends focused on prep work for school.

In each place that I lived, I was very mindful of the public, fundy-queer performative identity I was constructing for myself. At the risk of being extremely reductive, “performativity”—a phenomenon whereby a social identity is constructed primarily through a verbal, authoritative act— has been a term modified and indirectly redefined many times through the past decades, varying from academic disciplines, so it’s extremely challenging in the limited time that I have even to relay a concretized definition from primary sources. Essentially, its roots come from speech act theory, a linguistic approach to understanding the relationships between spoken words and action, specifically focusing on three parts: a) the literal spoken words (locution), b) the author’s intent (illocutionary force), c) and how the author is actually perceived (perlocutionary effect). For the purposes of my narrative, I want to consider my fundy-queer performativity as the socially agreed-upon conservative identity I assumed and performed for myself primarily through my religiously conservative speech and actions, for example, teetotalism at university parties, etc. because I knew that was the expectation for what a fundy-queer should act like. But even more so, if we are to assume that any performative act of social identity requires an authoritative stamp of approval, I would argue that the fundy-queer finds his or her approval through (his or her interpretation of) God and the Bible. I cannot think of a better example of this paradigm than the popular 70s gospel song, “God Said It, I Believe It.” If we were still following the original structure of speech act performativity, we could say that the fundy-queer’s interest lies primarily in the locution portion of any speech act, in this case, theological decrees spoken in times past and then written down for perpetuity, completely bypassing any questioning of the author’s intent or illocutionary force. And so it was for me. Even though I was over 700 miles from home in Texas, I still found myself reverting to my fundy-queer performativity. Perhaps I could have started over with a new persona, but I was still not proud of or even wanted to internally recognize my gay-queer identity. The following journal entries represent my desire to maintain that fundy-queer performativity while also recognizing that my physical presence (or absence) at church was not a convincing enough nonverbal speech act even to myself.

10:08pm 6/27/02

Tonight I found myself abysmally on the opposite side of the church mirror. I got a message that [my Sunday School Teacher and his wife were] coming over for a visit—Hello—that’s [a] Sunday School Teacher’s way of saying you haven’t been coming to church—and that’s true—I haven’t come in 3 weeks. I feel so guilty about that. [. . .] All in all, I think they had a pleasant visit. They said that the class was going canoeing in July—I’ll definitely be going to that. [. . .] Anyway, [their] visit was successful. I’m not going to skip again.9:02 am 7/7/02

I’m getting ready to go to Sunday School—but I feel it’s just for show. I feel like I’m throwing my life away for a life I’ve always heard preached against, a life I know holds no profitable value for eternity. I have too much of a conscience to enjoy my double life or clandestinity. Sigh. I have a feeling my studies are going to be much tougher with these distractions. Will this October be my last—or—like it was 3 years ago? Wow—already 3 years. [. . .] God—just kill me. I’m falling apart anyway.

Again, as I mentioned earlier, after my expulsion, I began questioning what my purpose was in living. Why would God keep me alive if I had been taught that there was a “sin unto death”; and what worse sin could there be than being an “abomination,” as I had been told so many times from the pulpit? Especially in my second entry, the binary of my conflicted, compartmentalized identities becomes evident: public fundy-queer vs. private gay-queer. But unlike before when I experienced the uncomfortable convergence of both my queer identities back in 1999, in Texas I began to discover that on certain occasions (probably more than I was even aware of), my fundy-queer performativity was not convincing or authoritative enough, but instead served only as an ineffectual shield over my gay-queer self. In my next journal entry, I recount the details of going to Dallas to attend the birthday party of a grad student—who I’ll call “Z” out of respect for her privacy—I got to know over the course of a semester while we took a class together. We weren’t super close, but close enough for her to invite me to her party, which was over an hour away from where I lived. (I should pause here and say that I am normally reticent to use the word “fag” in conversation, but I think it will be evident from reading the entry why I’m using this actual word.)

7:48 pm 11/24/02

Last night at [Z’s birthday party], I had quite a surrealistic shock. [. . .] [Z] was surprised to see me. [. . .] She brought her friend Scott, who is a total fag, self-acknowledged, and who was a little cute. [. . .] Anyway, halfway through the party, I went to help [Z] with the drinks, and she said, “You know what I am? A fag hag.” I was startled because I had a feeling she was including me in that group of fags. I didn’t know what to say. I sort of was just gonna let her think what she wanted. Then, as I’m getting my picture taken with [Z] cause I’ve got to go to [meet a guy] and do what I claim I’m not doing[, Z] explains to the girl who took my picture that I’m the guy she was trying to fix up with James. I was like, OH MY WORD! She was thinking of me. I didn’t know what to say again. I sort of walked away, and I didn’t think she caught on about my confusion, but apparently she did. She said, “I noticed you got really quiet. Are you gay? I guess I’ve never asked you.” I said no I wasn’t, feeling very hurt and ashamed and transparent. She apologized and then said I acted feminine and that her other friends there were gay. She wasn’t insulting me, just judging from a semester’s accumulated evidence [of] my actions. I don’t get it. I’ve been trying to work on my voice and my posture, yet she still thought I was gay. Lord, how can I change fingerprints? I am wandering in sinful quicksand.

I doubt that my words convinced her of my being straight, but as much as I knew she would have accepted me for being gay-queer, the fundy-queer part of me would not even allow me to utter the words that I was gay: my gay-queer performativity seemed to belie my fundy-queer one, even when I tried not to give it any authority (through verbal acknowledgment) in constructing my public identity. All the same, I wrote about this continued frustration of my battling queer identities near the end of my time in Texas.

11/11/03

I am a broken, disassembled, irrational, mentally-

psychologically-deficient something of a man—

a man through the letter of the law

solely through genetics

xy by curse

hexed to be given a y

instead of another x

blah blah blah

Quit crying over yourself and this broken identity.

You’re becoming less of an individual anyway.

What I find really interesting about this “poem-rant” is that my self-loathing or dissatisfaction extended all the way down to the chromosomic level, as if my same-sex attraction could’ve been averted had I simply been born a woman instead of a man. I think this is why I had such a recurring “broken” imagery throughout my writings. Though I knew I was not completely serious in my desire to change genders, I must admit I did entertain the notion, wondering how much easier my life would have been. In my ignorance, my fundy-queer self bought into the essentialist notion that all men “naturally” have an attraction to women, and if I did not have that attraction, somehow my notions of gender identity were warped. (This line of thinking is certainly not unique to me. For more than a century, sexologists referred to this as “sexual inversion.”) Conversely, the gay-queer side of me grew fearful, ignorantly applying the same essentialism in reverse: having certain mannerisms or flamboyant personalities automatically made me gay-queer. I found myself in an identity impasse.

Over the course of seven years, I lived in Texas, Michigan, Germany, and back to Michigan, always trying to find a church, but never successfully joining one. On Sundays, especially as the Facebook age dawned, I knew I should remain off the grid during church times so as not to tip off my family or IFB friends that I wasn’t regularly attending any church. Furthermore, this cycle included personal disappointment: I would promise myself that the new move and fresh start meant a commitment not to meet guys in the area, but this promise would invariably be broken within the first few months. While I was experiencing the same old identity clash during each move throughout those seven years, I also found myself achieving positive things in my career. I received a Ph.D. in English, I was gaining great teaching experience in a big university, I started to develop networks of likeminded scholars and researchers at conferences, and I even managed to secure a Fulbright Fellowship to Germany. If I couldn’t be proud of my personal failures, I figured I could at least be pleased with my professional track record. And secretly, I smiled to myself, because in a way, getting my accredited, terminal degree elsewhere felt like a giant, Shakespearean “I-bite-my-thumb-at-you” kind of moment to BJU. It was as if I were saying, “Look at what you discarded!” Maybe in some small way, my expulsion gave me that drive to make sure I found a career.

And then—it happened. In the fall of 2008, I finally found a permanent job in South Carolina. This was serious for me, because it meant that after all that time of living temporarily in various places for 1, 2, or 3 years at a time, I could finally “settle down.” I was determined that this time I would find and stick with an IFB church. And that’s exactly what I did. It took me a few months, but I finally found one that was small and a tad rural, but it definitely felt like home. The people were nice and welcoming, and the music was fantastic. I soon became heavily involved with the music ministry. And for awhile, I really felt like I was where I needed to be. But then, the gay-queer part of me crept in, and I began to recognize that it wasn’t going away. About halfway through my time at the church, I had settled into my regular routine of compartmentalization. But while there may have always been cracks in the fundamentalist façade for me, I recognized by the middle of 2011 that they were growing.

When I think about it now, I don’t really know how much longer I might have stayed within the IFB enclave. After all, by 2011, I was comfortably positioned in a career and a church. The memories of October 1999 were long behind me. And, contrary to what you may think of my mental state in this present narrative, I really was quite functional in most settings and had learned to occupy social spaces without upsetting the fundy-queer persona I had worked so long to create, a persona of one who only clandestinely pursued his gay-queer side. But even though I was comfortable there, I was also getting older. I cannot tell you how many prompts or nudges I received from friends and church members about how I wasn’t getting any younger and that I needed to find a wife before it was too late. In response, I would laugh a little and thank them for their concern, but if I were really honest with myself, I knew that I could simply remain passive on this status quo path of attending this IFB church until one day I would realize I had become that single guy in his late 40’s at church about whom everyone always has questions. While I recognize the powerful ideological constraints I was under, in some ways, I feel like I was complicit in my own social and emotional infantilization because it was much easier to remain in an IFB church where I was comfortable rather than to ask the tougher questions about myself that I needed to answer. Thankfully, several outside influences served as a catalyst to make this transition from the IFB possible.

In my experience, I have learned that there is no easy way to directly ask a fundy-queer if he or she is gay-queer. No matter how affirming, considerate, and professional the question is when presented, that person may take it as an affront and shut down emotionally, or there could be an outpouring of unbridled emotions that prohibit a discussion. Either way, that question puts the person in a vulnerable place. But that is not to say the question shouldn’t be asked. In March 2011, I was in such a position. A friend I knew online delicately mentioned in a private message that there was a community of gay BJU graduates and that he could tell me more about that if I were interested. He added that if he were incorrect in assuming I was gay, he deeply apologized and I could simply ignore what he said. I remember feeling like my heart had frozen. The implications were staggering: who else suspected the truth about me, and how had my online persona betrayed me? Ultimately, I didn’t respond to him because of my busy work schedule and a healthy level of fear. I simply shut down on him. I acknowledged him publicly to let him know I was still friendly towards him, but I was too scared to do anything beyond that. But then, last June, I accidentally came out to my first professional colleague and friend, laughably because I unsuccessfully tried to play the gender-neutral game with him in discussing someone I liked. It was a groundbreaking moment for me, one that I wasn’t completely thrilled about, but after the initial shock, I came to accept that this was the trajectory I wanted to continue on at my own pace. In October 2011, I resumed the conversation with that same friend who approached me in April, and from there I began to connect to others like me who had gone to BJU. I am not overstating when I say that I became obsessed with hearing everyone’s stories. It’s all I wanted to do. I had thirsted for this kind of camaraderie for so long.

After that point, I knew that my time in the IFB was coming to an end. I constructed a mental timeline of how it would be done. Over Christmas, I would tell my family that I am gay, and when I got home, I would tell my church. I cannot convey how nerve-wracking both of those actions were. When I came out to my family this past Christmas, it was a shock, a rift in an otherwise wholesome, drama-free dynamic for as long as I’ve known it. I remember my mother remarking that it probably was a good thing I had not told the truth so long ago when I first returned home in October 1999. I didn’t have time to ask her to elaborate, but it did make me think that it truly would have been so “inconvenient” for all of us at the time, and it made me wonder if I would have even been allowed back home. In some ways, this blog is a post to them as well, serving as an explanation for where I’ve come from and why I’ve felt like I’ve had to hide who I am for so long. But even with the mutual understanding of our unconditional love for each other, it has been extremely frustrating on both sides: theirs for wanting to engage in a genuine dialogue, and mine for being mostly silent, unable to process and formulate what I thought needed to be satisfying responses to their questions. While I don’t claim to have all the answers now, I am at least working towards finding my own voice, and I hope that this helps them understand me and why it’s taken me awhile to write about all this.

As for announcing to my church that I was leaving because I was gay—well, that didn’t turn out exactly as planned. Several members did reach out to me, though, and for that, I am very appreciative. Others responded a little more negatively, which was understandable. As the early months of 2012 progressed, the news of my coming out spread to my extended family, with whom I’ve always had a positive, close relationship. Sadly, their responses were hurtful. One close relative berated me over the phone because I supposedly let myself be surrounded with ungodly influences, implying that I was at fault for my own “sin” and that I had not done enough homework before coming to the conclusion that I was gay. There was a period of time in January and February when I began to fearfully approach my mailbox because it seemed that every few days I was receiving a letter from a “concerned” relative. These letters all had a common mission: to “lovingly” tell me how much they were grieved by “my horrible choice”—the classic example of what is informally known as a “hug slug” message. I was astounded by the level of hurtful things they were telling me. The letters included sermon outlines from their churches and passionate pleas to reconsider being gay. As a warning, one family member sent me several pages of HIV paraphernalia, as though all gay people have it.

a panel from Jack Chick’s cartoon tract Angels, depicting AIDS as a malicious “wedding present”

Incidentally, this reminded me again of a Jack Chick tract I had read as a child, this one called Angels?, which intends to didactically show “the perils of rock music.” It was the first time I remember hearing about AIDS. In this panel, it’s given as a punishment for rebelling against the master plan of the band’s manager, but I remember being cognitively unable to identify the sarcasm of the band manager or envision AIDS as a discrete, microscopic entity when it was being described in the tract as a wedding present. Another relative sent me a scathing indictment about my dishonesty and also mentioned the dangers of AIDS. Here is an excerpt:

We all have choices to make—Some are irreversible when it comes to med[ical] treatment. I have no way to deal with you if you don’t believe in the Bible. You have no “plumb line” to live by. Only gray areas—you have no black and white, just sin or salvation. You are a sinner with a terrible addiction that you choose to ruin your life—as an alcoholic, druggie, prostitute, thief, robber, convict. I will continue to love you and pray for you always. I also hold you accountable for those you have follow your life style.

Love,

XXXXX

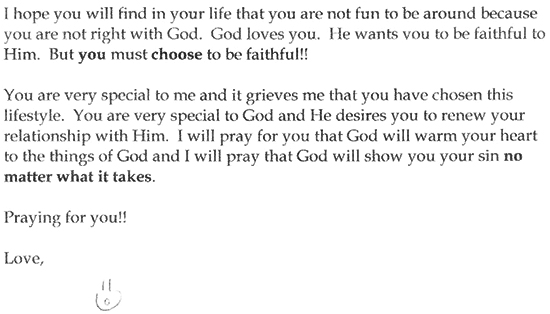

I especially appreciated how this relative concluded that he/she was no longer able to communicate with me and relegated me to the same category as “druggies.” The “hug slug” letters continued, where one relative remarked he/she was praying for me but hoped I would not be fun to be around until I have changed my ways. I particularly wanted to share the second half of the second page of this letter:

excerpt from a relative’s letter — a classic “hug slug” response to Lance’s honesty

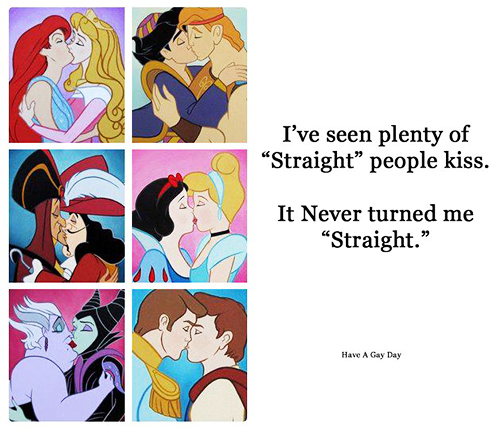

I have redacted the actual signature because it is not my intent to call anyone out publicly, but I just had to leave that smiley face in because I thought it represented so nicely the sharp shift in tone, starting with the rebuke and the thinly veiled threat “no matter what it takes,” then leading to the smiley face, which I couldn’t help but read in the following way: “I hope you have a terrible car accident so you’ll remember that you’re away from God. Love ya! Smooches! Bye!” I guess I was supposed to have a miserable demeanor and consequently realize that, because no one wanted to hang around me, something must be wrong with how I was living, which would then prompt me to change my ways. It was all pretty alarming, considering for so long I had been a part of their honorable “inner circle.” Even more bizarrely interesting was that their responses as a whole were divided and contradictory: either I was born with this “struggle” and needed to seek spiritual help to continuously suppress it, or it was learned behavior that I had picked up from who knows where, “unsavory” people perhaps, and I had been brainwashed because of my friendly, vulnerable personality into thinking that this is “acceptable.” As this extremely fundy-queer pastor would have people believe, I had been “recruited.” This is the part that really puzzles me: the idea of being gay as a pathology. Not only is it viewed as a terrible sickness (i.e., being unnatural and repulsive), but it’s also represented as something contagious. In my children’s literature class, we are currently discussing Jack Zipes’ essay, “Breaking the Disney Spell,” specifically when he notes that Disney shows only heteronormative relationships and how that reinforces the particular vision of Walt Disney. I recently saw a picture on Facebook where well-known Disney characters were modified to be in a same-sex embrace/kiss.

Do Disney’s heterosexual love stories “turn people straight?”

Obviously, the intent is to shock, but more importantly, the message is clear: watching hetero couples kiss did not make me any more desirous to kiss someone of the opposite sex than it would make a hetero want to kiss someone of the same sex. We typically talk about how acts of affection like these are construed as sexuality-based only when they visibly occur outside the heteronormative parameters. In other words, had this been a picture of Cinderella kissing Prince Charming, no one would be shouting “Too Much Sex!” with alarm. All in all, it has been quite a revelation to me how some members of my extended family categorize “unpardonable” sins, and it made me wonder if they pursued with such zeal this same level of concern to people in our family who have gotten divorced through the past years. After all, the Bible doesn’t look kindly on that, either, right? As the months progressed, I began to withdraw because I knew I couldn’t provide theologically satisfying responses to any family member, and I began to wonder, “Was all of this coming out even worth it?”

2 comments

Thank you, Lance. This is unadulterated bravery.

Being yourself is always worth it 🙂 The freedom experienced from such an act is what makes for a happy life. I long ago purged those from my life who couldn’t except me, even to the point of returning letters back to the sender unopened. If only those “Christians” knew what it was to really love.