Part 5: Late Bloomer and “Happy Endings”?

Read Part One Read Part Two Read Part Three Read Part Four

Lance Weldy, Ph. D.

And now, it is October 2012, a very significant month for me in times past, both in 1999 and 2011, and this year it is enormously memorable for me in how I publicly shared my story online throughout this month. Even today, near the end of my blog-publishing experience, I find myself only beginning to see the convergence of both of my queer identities in positive ways. Like Rachel Patrick mentioned, I never considered myself the activist type: in addition to being taught that civil disobedience was a fundamental “no-no” to the higher powers as referenced in Romans 13, to do so also meant that I would have to publicly implicate myself as gay-queer. But what some people may euphemize as “militant activism,” I have come more to recognize as simply a stance of “gentle openness,” an awareness that honesty and acceptance of my past and my present is not presented as a rhetorical means to blaspheme, but rather to expose the spoiled, ideological self-hatred we in the IFB were spoon-fed since childhood.

My mind goes back to that poem about the Titanic I referred to earlier: “The Convergence of the Twain” by Thomas Hardy. I believe the two major players in the poem, the ship and the iceberg, represented my two queer identities. In October 1999, I thought the ship represented the foolishness and detrimental nature of my non-heteronormative self, but now that I think more about it, I realize that the naturalness of my gay-queerness is the iceberg, and it will always stay as a constant part of my identity. But that doesn’t mean that the doomed ship represents all of my faith; rather, it is only the fundy-queer part of me, portions of which will always be with me as part of my cultural upbringing.

Alien they seemed to be;

No mortal eye could see

The intimate welding of their later history

As I read these lines from the poem more and more, I think about the providential nature of that historic event and also of how faith remains a part of me. Happily, BJUnity has served as a positive representation of the convergence of the twain, helping me on the steps of reconciling my faith and sexuality. I am still a believer in the self-less, saving grace of Christ, and the inherent desire to imitate that love towards others. On some of the other details instilled into me from the pulpit, I’m not so sure, but what I do hope is that my story can inspire others to share and seek comfort in their gay-queerness, especially those within religious circles.

Sure, I could provide refutations to the “clobber passages” that fundies use as a first round of defense against spiritualizing and affirming queerness; I could inform them how the book of Romans’s cultural milieu addressed the contemporary practice of sexually-based idolatry, and how, as Michel Foucault notes, sexuality as an orientation is a modern social construction unknown to those of the New Testament era (page 105); I could point out the double standard of fundamentalists when they shun such awareness of cultural milieu in Romans chapter 1, yet ascribe to it when discussing the watered-down wine or the biblically-sanctioned slavery of the New Testament; I could remind fundies that Jesus Christ may be “the same yesterday, to day, and forever,” but contemporary cultural views on the subjugation of women in the New Testament should make a biblical literalist blush at the scoffing of people like Joyce Meyer, who apparently violates the very scriptures by her ministry; I could mention, as Nelson puts it, how “because we are thousands of years distant from the language and culture there is no guarantee that our hermeneutic, our framework for understanding, will ever truly match the mindset of the author”; I could question the biblical soundness behind a fundamentalist’s ability to conveniently accept the ethos of a divorced/remarried pastor; finally, I could also mention that many fundies would happily defend a pastor accused of sexually abusing his position of authority while at the same time staunchly separate from or “unfriend” a man whose only crime is his same-sex attraction; but I don’t think any of that would be a good use of my time: fundies are taught to be anti-intellectual and instructed to follow their church’s or pastor’s interpretation of a translation.

Besides, I know there are many far more capable and knowledgeable people out there who could present compelling arguments for understanding and affirming queerness from a religious perspective, such as Matthew Vines. (And quite frankly, I’m not sure I have the energy right now to even begin such an attempt.) But like Mr. Todd notes in the recent New York Times article about the wonderful movement that Vines is ushering in, I am not sure that those in “leadership in the conservative Christian communities” will even listen. But that doesn’t mean we can’t question the paradigm for those who are more willing to listen or who are living on the fringes of or even exiled from the Christian community.

As John Shore recently depicted in his Socratic narrative between angels, it becomes confusing to digest the rhetorical responses from fundamentalists in regards to how to categorize the essence of being gay-queer: if it is a struggle we are naturally susceptible to (in the same category they would put alcoholism) that we must fight all our lives, does repressing this same-sex attraction make us any less gay-queer? Even recently, the BJU student newspaper, The Collegian, addressed this question—the writer calling it a “temptation” and equating it to other “secret sins.” (I thank God I never had the opportunity to enroll in an ex-gay program. I shudder at the horror of those who had to endure such ghastly methods of a promise that could never be delivered. As Curt Allison, and even the president of Exodus International himself, has admitted, ex-gay programs don’t change or transform; they simply suppress with intent to reform.) Alternatively, if it is a choice (of “lifestyle”), then shouldn’t we have an ability to quell any decisions to be gay-queer? In my twenties after being expelled, I was relieved to be, at least for a season, through with the lies. I thought that by implementing extreme self-restraint and having no interaction with guys, I was able to maintain an honesty with God, my family, and myself. But this was a false honesty, an honesty fettered. In a weird way, I fooled myself into thinking that I could remain honest about not being gay-queer only because I remained temporarily celibate. That was no way to live or to be self-aware. Now in my thirties, I realize that true honesty is coming to accept myself as gay-queer so that I don’t have to be ashamed or hide from all of the questions, or compartmentalize the Christian roots from the queer identity. As David Levithan has said, “being gay is not an issue[;] it is an identity. It is not something that you can agree or disagree with. It is a fact, and must be defended and represented as a fact” (italics in original). Should it be any surprise then that I am hesitant to re-immerse myself into a church community when I have been told since childhood from the pulpit that a very huge part of me is an “issue” that God finds abominable rather than an “identity” I can be proud of? (That is not to say that I still don’t identify as a gay Christian. As I said earlier, the fundy-queer portion of my background is not completely equated with the Christian religion as a whole.) Nevertheless, because the church culture was such an influential part of my background for over 20 years, I cannot say I will never re-enter it, but I want all readers to be aware that it can happen for me, and that my hesitancy as a part of my healing process should not discourage others from active involvement in the right church.

Near the beginning of my narrative, I labeled myself a Late Bloomer. Aside from accepting the phrase’s traditional references to delayed physical maturation which I do not need to describe to you now, I have actually found time to reflect on how I’m a Late Bloomer in terms of my mental maturation, specifically in developing critical thinking skills which (surprisingly) did not happen until after my time at BJU. It’s funny, because while I have subtly always viewed myself as a Late Bloomer, it was not until a few years ago, well after I had finished my doctoral work in literature, that I had heard that one of the senior English faculty at BJU referred to me as a “Late Bloomer” out of surprise at what I had been able to accomplish in the academic world. Apparently, either my academic track record or class discussions or overall reputation while at BJU hadn’t left such a promising, intellectual impression on him. Who knows. But, I had to laugh at this, because it is a term I actually embrace. To me, it makes me smile, knowing that I didn’t have to remain what they or anyone else there thought of me. And there are still many ways I am perpetually maturing as a result of coming out, specifically on an emotional-social level. For example, back in the spring, I had a conversation with another member of BJUnity who, while extremely appreciative of all the posted biographies, found it challenging to see himself in the stories because many of them concluded with some sort of personal relationship success with a partner, which is certainly appropriate and heartwarming. As someone who has never had a traditional boyfriend or relationship, I had to admit this was something I too had noticed. Interestingly enough, a discussion with a colleague just this past week served as a reminder of this kind of emotional infantilization. As part of her classroom conversation about The Great Gatsby, she asked her students what constituted a dating relationship, such as intensity or drama. As she relayed her student responses to me about their personal experiences, it dawned on me yet again that I have no frame of reference whereby I could have participated in such a conversation: my clandestine gay-queer self prohibited my ability to be in any traditional relationship. I was socially stunted. But I looked at the conversations of this week and last spring from the perspective that we are not all operating on the same timeline, nor can we be expected to, and this perspective should be all the more reason to tell our own stories as a matter of making our variety of situations more visible. Ultimately, the heterogeneous nature of our gay-queer community is such that even though there are universal identifiers within each story whereby one can find a semblance of self-identification, no story can be duplicated exactly, and that is what gives us such wonderful variety. As such, my narrative doesn’t conclude with a happy ending that I’ve found a partner. To be honest, I never thought it would be in the cards for me to even be in a position to look for a significant other: as someone who felt broken, I considered myself unworthy of a relationship; specifically, as I mentioned earlier, I never really saw anyone in gay media that resembled my station in society, my interests, nor my looks; but also, more importantly, I never thought it could be acceptable for that significant other to be a man instead of a woman. And of course, this is all operating under the assumption that happy endings even require having a significant other, a concept we talk about in-depth in our Cinderella unit in class. In high school chorus, I distinctly remember singing an excerpt from that song, “People,” for a medley we were doing. I never quite understood that lyric: “People who need people are the luckiest people in the world.” Really? I never wanted to open up and be that kind of emotionally-dependent “people.” But now, I find myself intrigued. Maybe it would be nice to have someone, to be someone’s. Or maybe I will discover that my introverted self precludes the possibility of a long-term relationship. I’m not sure. But now that I’m honest with myself about what I want and can potentially have, at least I know I could have a better shot at it.

A few months ago, while at a party with fellow faculty members at the state university where I teach, the conversation shifted to discussing the sexual orientation of certain students on campus. One of the people quipped that a certain student was “too Christian to be gay.” And while the comment was said in a tongue-in-cheek fashion, it stuck with me, because what he said was all too true for people like me, and it appears that there are currently students like me in similar situations on my campus and in the area. During that conversation, and even recently, whenever gay-queerness comes up even remotely in any conversation, I instantly look down and feel my cheeks burning, refraining from even participating in the conversation for fear of implicating myself inadvertently, especially when I’ve fought so long to stay hidden. Until now.

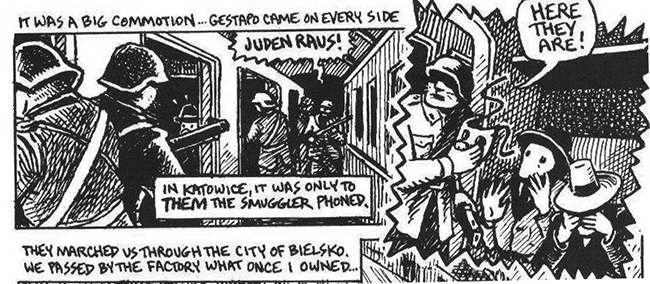

a panel from Maus

Last semester, I taught Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust graphic narrative Maus, and throughout the story, Spiegelman uses anthropomorphic animals as metaphors for different ethnicities or nationalities: Jews are represented as mice, while the Germans are cats, etc. And while I wouldn’t dream of comparing my personal experience with the persecution of Jews, I feel I can identify with the motif of the mask Spiegelman implements as a measure of hiding the characters’ Jewish identity during the story. In one scene, the protagonist and his wife are trying to escape oppression by wearing pig masks, which represented the Polish. I’ll never forget the scene on page 155 when their masks were removed by the Nazis.

I kept thinking to myself that my mask could be removed at any time without my control. Fortunately, I knew that I would not face any serious persecutions at my job, or any real severe physical repercussions (unless, perhaps, I found myself in certain rural pockets here in the South). What remained a fear was perhaps on the emotional and psychological level, and to combat this, for me, I wanted my mask removal to be done on my own terms on my own timeline. And that’s what I’m doing for you now: removing my own mask. (When I shamefully moved back home in 1999, I was in no wise financially independent and could not remove my mask for fear of all kinds of consequences, including the loss of shelter, so I think about those who did not have a choice, like Jonathan Nichols, and cannot even begin to imagine the amount of courage and strength it has taken people like him to pursue his goals, especially at such a young age.) As Richard Rodriguez notes, “Growing up queer, you learn to keep secrets as well. In no place are these secrets more firmly held than within the family home” (page 326). It’s more than a little scary, but I know it’s time to release those secrets, and in some weird way, it feels good knowing that it’s time. But just as I did not have that quintessential happy ending that I mentioned above, so also did I not have what I call that “hallelujah moment”—that euphoric feeling of unbridled liberation and peace, the unquestionable sense that I’m doing the right thing—that so many others said they experienced as soon as they came out. Instead, mine was a very tumultuous time at the beginning; for many months early this year, I felt somewhat stifled because I had come out only to a few people. I just didn’t feel ready to take that next step, partly because I knew I needed time to process where I’ve been, and partly because I knew it would take quite a bit of time to write this narrative. But now, this blog marks the final stages of my coming out, and for me, at least the fear now was not in wondering if I’m making the right decision, but rather what would happen now. I am happy to report that my “hallelujah moment” has finally come. I cannot begin to explain the power of all the positive responses I have received throughout this month. I know many people have scrutinized the superficiality or triteness of the “It Gets Better” campaign, but for me, I now understand its message. Of course, I still have struggles and my family and I still need to have some serious conversations, but I think I’ve gained confidence and self-assurance, definitely two much-needed assets to serve as a kind of antidote for the self-hatred long present in my life.

And now, as I bring my narrative to a close, I realize that in a way I’ve come full circle. As I mentioned in my Preface, I was fearful about my two queer worlds colliding, especially paranoid that any students would find out about my story. Well, that event has already come to pass during the first week my story was published: a current student stopped by my office and complimented me on my blog writing. I have to admit it was a shock at first. The blog had only been up a few days. But after a few minutes, I realized I could handle it. Public is public, and as oblivious as I am to what people notice of me, I had to understand that my story would get out to all kinds of people eventually. Since that incident, I have been aware of other students following my story as well; I felt no fear like I thought I would. It was nice not to worry.

Lance Weldy with David Diachenko, Justin Van Leeuwen

and others at SC Pride, October 20, 2012

2012 has been a year of gay-queer milestones for me. If you would have told me a year ago that I would be marching in 3 different Pride Parades with other members of BJUnity this year, I would have laughed in your face. Like Rachel Patrick, I too “never wanted to be one of the PRIDE kind of queers.” To me, Pride simply represented all the stereotypical decadence that I wanted to avoid, that I remembered from Jack Chick’s Wounded Children. But instead of decadence, I found substance. It wasn’t until the most recent Pride last weekend, South Carolina Pride, that I discovered just how potent the fundy-queer side of me, my deeply-sunk Titanic, could still be. Our walk along the parade route began like the other two, without much controversy. It wasn’t until we rounded the last corner of our path headed towards the capitol building that I noticed something different. Somewhere from my left, I thought I heard my name. I was incredulous. There were hundreds around me, blended noises. How could I have heard anything so specific? And that’s when I saw them: an elder and the pastor of my former IFB church—the one I had left in January—both standing in a long line of protestors that stretched all across the front of the capitol. In their hands were anti-gay posters, which I expected. What I didn’t expect was the direct look of shame at me from my former pastor. In an instant, my stomach sunk and memories flooded. Unlike the other two parades I had attended, this one became uncomfortably personal in such an unexpected way. All I could think of was how much had changed in a matter of months, how a year ago I was practicing the Christmas cantata with the church choir as a revered fundy-queer, how the last time I spoke to my former pastor was in January when I left the church, and how bizarre it was that we were now on opposite sides, opposing sides. I shut down for what seemed like minutes, but eventually I came back to my senses. The shock slowly wore off, and I received emotional support from my fellow marchers. I had a good time the rest of the day, but all this week as I have been thinking about my final post, I kept debating whether I should include the picture from Bill Ballantyne that captured this moment so powerfully. I certainly do not want to call anyone out, so I have decided to show the picture without revealing which one is my former pastor. Showing the picture should be enough to convey the dramatic tension and to reveal what fundy-queers stand for.

Lance Weldy and Paula Bass at an ice-skating event with a group of fellow BJU graduate assistants

There were so many times during the drafting of this narrative where I would initially write, “I have more to say here, but I can’t right now.” Because of the constraints of this medium, I knew I couldn’t test the reader’s patience, that I had to refrain from going into so many other events and details. But I will say that this kind of writing has been the most challenging and rewarding for me, and it is my desire to continue this project in some way, perhaps to compile extended narratives—from those who have and have not already written their story down—for a publishing venue more appropriate to extended narratives, because I feel strongly about our message—that we are not alone: not alone in our struggles for socially-constructed normalcy, not alone in our shame for failing to find that normalcy, not alone in our desire to understand who we are and to find comfort and courage in our identities. I have already relayed the sad, ironic trajectory of my friendship with Andrew Bolden. If only we had known about each other as undergraduates at BJU, what would we have done? Could we have encouraged each other? I’m not sure, considering the toxic environment of control and self-scrutiny we were constantly under. But, at least we would have known. Part of what BJUnity has done for me is to reveal how many other contemporary people I knew who were suffering in similar situations. Probably one of the most significant examples of this clandestine phenomenon is with my friend Paula, who used to be Andrew’s and my boss during our undergraduate years, and who soon became a friend I hung out with while a Graduate Assistant. How bizarre it was to discover recently that she was fired soon after I was expelled! Could we have been a support for each other in some way had we known about each other? Obviously, the encouraged snitching on campus would have made that highly doubtful, but what I am sure of is that each new story further cements that we are not historical, isolated incidents. Being gay-queer certainly did not stop with the conclusion of the 20th century, and there is no reason to believe BJU hasn’t continued the same tactics of controlled silence to this present day.

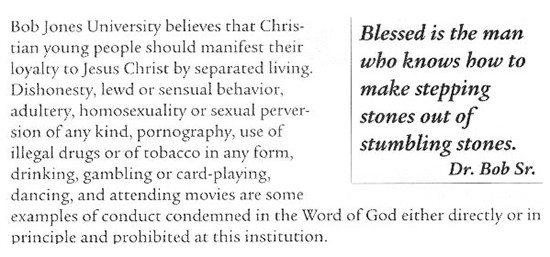

I think I am also coming full circle in this narrative because I will refer to the Student Handbook one last time. As I mentioned earlier, The Collegian has recently published an article about homosexuality as a “temptation.” For the longest time, I would have probably agreed with that statement. It was my personal stumbling stone that I held as a tightly-gripped secret inside me. I went so far as to build emotional walls around that portion of me. As I look back to the handbook’s discussion of what it means to be “loyal” to Jesus Christ (aka BJU), I notice their sweeping gesture of all things that constitute being outside of God’s will. I chuckle incredulously at how many “sins” on their list—including anything non-heteronormative—are classified as more cultural than biblical. And then I see the quotation from “Dr.” Bob Sr. to the side. His many sayings are well-known by students, not only by how they are sprinkled throughout the Student Handbook, but also because his quotations are plastered above the chalkboard in every class room in the Alumni Building. Ironically, the juxtaposition of his quotation next to the list of condemnations unintentionally evokes a comedic effect: this list of offenses—for that matter the Student Handbook as a whole—is itself a stumbling stone. But now, in October 2012, I am turning that book into a stepping stone with my story; for now, I am figuratively closing my Student Handbook. I may revisit it for research purposes, but it no longer holds the power I once gave it.

BJU Student Handbook 1997, Page 5 (excerpted);

includes a quote from Bob Jones, Sr.

As Ben Adam so eloquently puts it, “Usually, I am reluctant to write about [homosexuality] and how it relates to the Bible. Oftentimes, people rarely change their hearts based on ‘biblical’ arguments. Only personal stories with real affects truly change people.” Additionally, the subversive writer bell hooks notes: “To engage in dialogue is one of the simplest ways we can begin as teachers, scholars, and critical thinkers to cross boundaries, the barriers that may or may not be erected by race, gender, class, professional standing, and a host of other differences” (page 130). It is precisely for the combined reason of both of these quotations—telling personal stories to help readers cross barriers—that I hope my story and others like mine can invite a dialogue to do just that. It might be a result of my taking more of a reclusive approach to life because of my opposing queer identities, but there is almost nothing as powerful to me as knowing that someone is truly and actively listening to me, that I have a voice, and for me, though this narrative has been an intense, fearful undertaking, it is most gratifying just to know that someone is listening to it. I realize that “hits” on a website do not automatically equate to someone really listening, but I will interpret this blog venue as a forum automatically constructed for listening. My story may not be the most groundbreaking or have the most special-effects, and that’s okay. As long as you have taken the time to listen, I remain extremely gratified. Throughout this month, I have received so much indication that you have been doing just that. And for that, I thank you immensely.

4 comments

Powerful, compelling story Lance. Thank you so much for sharing!

Very moving, Lance. Thank you for sharing your story.

Growing up in a fundamentalist Christian high school, which in many ways was as strict as Bob Jones, I can somewhat relate.

The Gay Christian Network (gaychristian.net) has been a big help to me. Not trying to plug anything, but I encourage anyone reading this to check it out.

Thank you Lance. And thank you for being such a good conference buddy. I wish you every happiness in the future as you find you own way to celebrate your faith, your love of God and your love of people.

Hugs,

Lydia

How refreshing to hear a story that explains what i believed. Sent link to ex wife to help explain why I did what I did. Thank you so much for sharing!